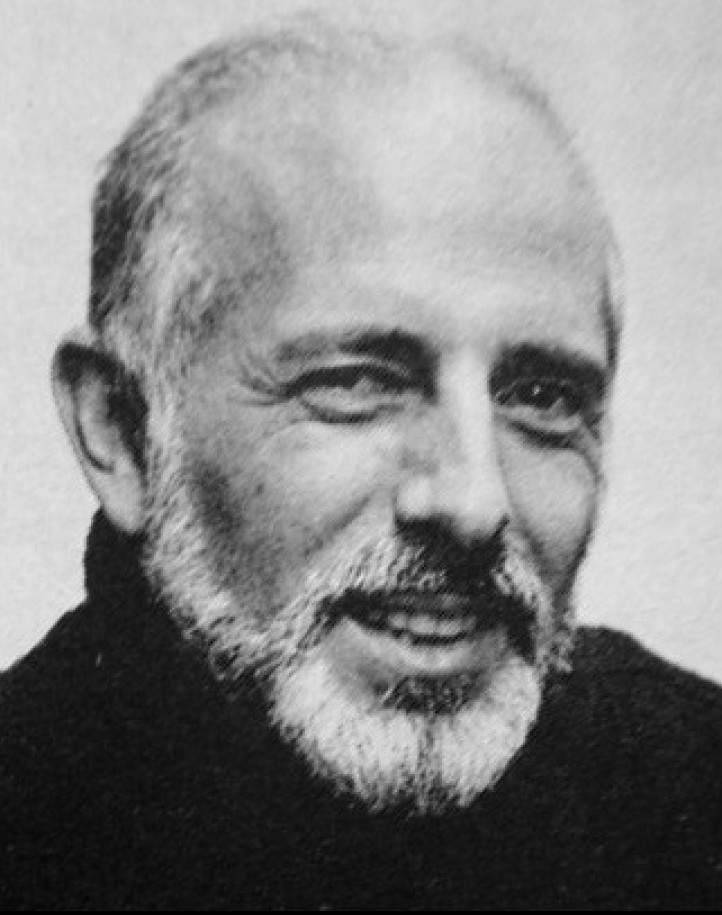

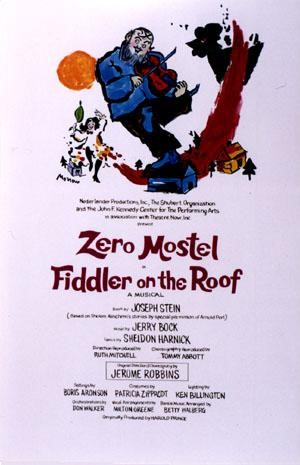

When Zero Mostel entered the Imperial Theater on Fiddler’s opening night, do you think that he knew he’d have a hit? Do you think that he knew he’d win Tony Awards and national praise for three hours’ worth of song and dance, or that it would be transformed into an Oscar-winning film? Do you think that he thought about how far he had come since 1955, when he was Blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee for his alleged ties to communism? It was designed to crush him, silence his art, and destroy his career, but still he could walk into the theater all those years later to inspire generations of audiences with his touching tale of love and tradition.

When Zero Mostel entered the Imperial Theater on Fiddler’s opening night, do you think that he knew he’d have a hit? Do you think that he knew he’d win Tony Awards and national praise for three hours’ worth of song and dance, or that it would be transformed into an Oscar-winning film? Do you think that he thought about how far he had come since 1955, when he was Blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee for his alleged ties to communism? It was designed to crush him, silence his art, and destroy his career, but still he could walk into the theater all those years later to inspire generations of audiences with his touching tale of love and tradition.

Getting to opening night still had its difficulties. Mostel and director Jerome Robbins had been enemies for nearly a decade because Robbins had also testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee and named names. In doing so, Robbins hid his Jewish heritage from the public, along with other personal secrets, and his career was left intact. Mostel on the other hand struggled to find any work, nearly forcing him to quit the business. Perhaps this gave him a deeper connection to Tevye through the song "If I Were a Rich Man."

Getting to opening night still had its difficulties. Mostel and director Jerome Robbins had been enemies for nearly a decade because Robbins had also testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee and named names. In doing so, Robbins hid his Jewish heritage from the public, along with other personal secrets, and his career was left intact. Mostel on the other hand struggled to find any work, nearly forcing him to quit the business. Perhaps this gave him a deeper connection to Tevye through the song "If I Were a Rich Man."

And yet in less than ten years, Zero Mostel seemed to do the impossible: From the career crushing blacklist for alleged communist ties, to playing a loveable communist sympathizer on the stage for the world to see, giving voice to millions of Jewish and Eastern European immigrants. Fiddler on the Roof became a cultural icon because of the juxtaposition of its material and its time.

Set in a fictional Russian shtetl in 1904, Fiddler follows Tevye, a poor dairyman, as he tries to marry off three of his five daughters. The arranged marriages, a traditional practice in his orthodox Jewish community, clash with his daughters’ desires to choose their own partners and marry for love. Tevye’s faith and tradition are challenged while he and the rest of the village must cope with increasing violence and discrimination from their Christian neighbors and impending political uprisings throughout the country. The family is ultimately forced to flee their homeland and travel to America to escape persecution. [1]

Set in a fictional Russian shtetl in 1904, Fiddler follows Tevye, a poor dairyman, as he tries to marry off three of his five daughters. The arranged marriages, a traditional practice in his orthodox Jewish community, clash with his daughters’ desires to choose their own partners and marry for love. Tevye’s faith and tradition are challenged while he and the rest of the village must cope with increasing violence and discrimination from their Christian neighbors and impending political uprisings throughout the country. The family is ultimately forced to flee their homeland and travel to America to escape persecution. [1]

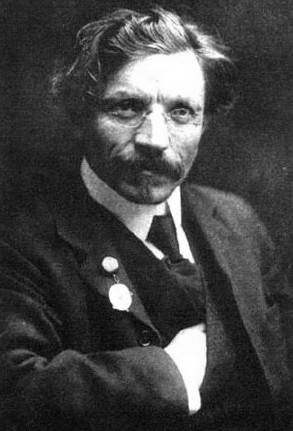

The musical is based on Tevye the Dairyman, a series of stories by Sholem Aleichem written in Yiddish between 1894 and 1914 about Jewish life in a lifeless village. Aleichem was born Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich on March 2, 1859 into a Hasidic Jewish family. His pen name Sholem Aleichem is a play on the Yiddish phrase “shalom Aleichem” meaning “peace be with you.” Aleichem wrote the chapters one section at a time, then publishing what he had created, rather than crafting a whole story and publishing one complete work. [2] This style of publication was very uncommon and caused him to develop stories with an unchangeable past. Stern describes Yiddish as a more colloquial speech pattern. It “would be understood by the noble Russians as well as the Jews at the time…and gave Tevye a much friendlier demeanor.” [3]

The musical is based on Tevye the Dairyman, a series of stories by Sholem Aleichem written in Yiddish between 1894 and 1914 about Jewish life in a lifeless village. Aleichem was born Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich on March 2, 1859 into a Hasidic Jewish family. His pen name Sholem Aleichem is a play on the Yiddish phrase “shalom Aleichem” meaning “peace be with you.” Aleichem wrote the chapters one section at a time, then publishing what he had created, rather than crafting a whole story and publishing one complete work. [2] This style of publication was very uncommon and caused him to develop stories with an unchangeable past. Stern describes Yiddish as a more colloquial speech pattern. It “would be understood by the noble Russians as well as the Jews at the time…and gave Tevye a much friendlier demeanor.” [3]

Before 1964, Broadway productions had been almost exclusively musical comedy. While opera and operetta are the ancient ancestors of musical theatre, its more direct origins date back to early American vaudeville and burlesque performances, which were small vignettes and scenes which included a few songs and duets. Following World War II, there was an increasing demand by audiences for musical plays rather than revues; they craved thoughtful plots with interwoven songs to progress the story. [4]

The 1960s saw the “malleable image of the Soviet ‘Other’”. [5] Few Americans understood the Soviets with any sophistication or complexity, which meant that a new collective memory of the Russians could be constructed almost at will. And this image was predominantly the Russian as “bestial, stubborn, abusive, deceptive, backward, barbaric, etc.” [6] This cultural definition problem became a question of the day for anticommunists.

The show found the right balance for its time, even if not entirely authentic, to become "one of the first popular post-Holocaust depictions of the vanished world of Eastern European Jewry." [7] When Fiddler began, the wounds from the Holocaust were barely twenty years old; The show concludes with allusions to these atrocities, when characters flee to Warsaw, Krakow, even Jerusalem. The fact that these characters fled one country of injustice only to relocate to another country where they aren’t welcome served to remind audiences of the centuries of oppression that Jews have faced globally.

Warsaw, Krakow, and Jerusalem—all destinations for the displaced populations. And yet by the middle of the twentieth century, they all became hotspots for culture clashes between Jews and natives. In Jerusalem—the Holy Land—and the rest of the Middle East, ethnic tensions between Jews, Christians, and Muslims began brewing. In other corners of the world, such as Warsaw and Krakow, the Nazi occupation of Poland and the subsequent systematic ethnic purge of Jews during the Holocaust became an indelible scar on human history.

Other characters flee to New York, during what would have been the peak of immigration during the turn of the twentieth century. According to Wittke, “…most theater composers were/are Jewish (usually second-generation) and they burst on the theater scene in the twenties.” [8] The story struck a cultural nerve for the creative team. The final version of the script is dedicated to “Our Fathers,” a reference to Bock, Stein, and Harnick’s fathers, all of whom were Eastern European immigrants to the United States in the early twentieth century. [9]

Additionally, most of the prominent financiers, audiences, and producers were Jewish. This cultural connection to the characters, their oppression and the plight of their ancestors, effectively became the immediate reason for its impact on Broadway; the well-to-do of the Broadway community knew the story all too well, and needed the rest of the world to see it. More importantly, it became a story that audiences could universally connect with, hence its astonishing success.

On September 22, 1964, Zero Mostel and the rest of his cast walked into the Imperial Theater without fully understanding what the ramifications of their work would be that night. As they warmed voices, adorned costumes, and shook out nervous energy, the curtain went up on what would quickly become a landmark show which changed the course of musical theatre. And in the morning, Fiddler on the Roof was a raving hit with newspapers and critics, citing Mostel’s brilliant mixture of humor and tenderness. [10] And yet during the height of the Cold War, mere months after climactic world events like the Cuban Missile Crisis, McCarthyism, and John F. Kennedy’s assassination, a show about Russian Jews with Communist sympathies still had a resonating message.

References

Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and Sheldon Harnick, Fiddler on the Roof. (1964): 91.

Sholem Aleichem, Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories. Translated by Hillel Halkin. (New York: Penguin, 1996).

Jeremy Dauber, The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem: The Remarkable Life and Afterlife of the Man Who Created Tevye (New York, NY: Random House, 2013), 88.

Edith Borroff, "Origin of Species: Conflicting Views of American Musical Theater History," American Music 2, no. 4 (1984): 107.

Andrew J. Falk, "Casting the Iron Curtain," Upstaging the Cold War: American Dissent and Cultural Diplomacy, (2010): 76.

Ibid.

Foster Hirsch, Harold Prince and the American Musical Theatre, (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Press, 1989): 71.

Paul Wittke, "The American Musical Theater (With an Aside on Popular Music)," The Musical Quarterly 68, no. 2 (1982): 277.

Joseph Stein, Fiddler on the Roof, 2.

Howard Taubman, "Theater: Mostel as Tevye in 'Fiddler on the Roof.'" New York Times (September 23, 1964): 56.